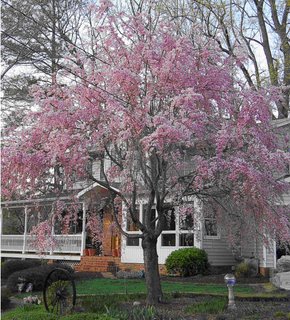

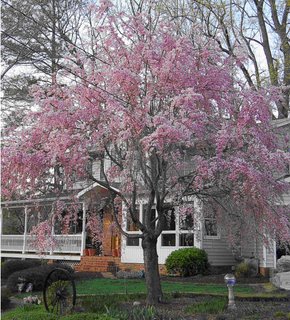

Going to get down to business, but first had to share this photo of the Cherry Blossom Festival that's taking place in my front yard. It's spring!

Going to get down to business, but first had to share this photo of the Cherry Blossom Festival that's taking place in my front yard. It's spring!

Wading In

Many of the bloggers I try to read regularly write about the future of classical music and its audience. I invariably have strong reactions to many of their posts - a combination of violent disagreement, "aha" moments, renewed optimism and sudden despair.

I've been deterred from entering into the fray because 1) I don't know where to start, 2) theirs are better minds than mine, 3) from what I can tell, my readers are more interested in the opera-specific tidbits that I post.

So there's no telling exactly why I'm wading in today. Maybe it's because we're in a 5-year planning process here at the Foundation... maybe it's because our box office opened last weekend and I'm already obsessed with how many tickets we're selling for opera and symphony.... maybe I just have to get it out of my system.

Who Needs Classical Music?

I've been re-reading Julian Johnson's exhaustive treatment of this subject - go here for the book. Be forwarned - it's not a simple read, but well worth it. Is it intensely academic? Yes. Are some of the assumptions born and bred in an ivory tower sensibility? Yes again. But it's unflinching and thought-provoking.

I find this somewhat prickly book reassuring and comforting. I have no idea why, for it offers absolutely no practical ways for reconciling the intrinsic value of music with the realities of our 21st century culture.

The Game Is Over

The blogger who's spending the lion's share of his effort on this subject is, of course, Greg Sandow over at Arts Journal, whose postings I've been reading for over two years. He's "performing" a book about the "Classical Music Crisis". The introduction to his book gives you an idea of the basic approach:

"I think the game is mostly over, by which I don’t mean that classical music will disappear, but that the classical music world will change, maybe drastically, and that classical music institutions — even big, brand-name orchestras and opera companies — that don’t change fast enough might collapse. "

I can't begin to fairly represent his many and considered thoughts on this subject (if this interests you, it's well worth setting aside an hour and browsing his book and his blog), but I will say that while his approach feels a bit combattative and argumentative, it does bring a welcome breath of fresh air and a much-needed wake-up call.

Sandow takes great issue with Julian Johnson's book, which isn't a surprise given their wildly different approaches. He, like Johnson, lives in a very different world from the rest of us. But that gives him a perspective that enlivens and enrichens this debate.

A Tradition in Flux

For a rebuttal, consinder Wellsung, whose essential approach is that classical music is a tradition in flux. He maintains that "there are doors closing, [but] there are also a lot of windows opening."

"Sandow's exercise is this: take the viewpoint of someone with no serious interest in, predisposition towards, or even attraction to the classical music tradition...Then mine the classical music experience for things which would maybe surprise the person who isn't interested and thinks its boring in the first place -musicians should dress down; play in a bar; bop around more while playing; the program notes should be less detailed; louds should be louder; softs should be softer; and the list goes on. And that's just the entertainment side... He suggests musicians and those who love classical music must: stop wallowing in its elitist trappings; stop going on about aspects too difficult for everyone to understand; and, especially, stop pretending its a more complicated or demanding tradition than pop or jazz."

I love the "lot of windows that are opening" part - more about that below.

Gray Hairs

No, not the ones I'm sprouting while grappling with this... rather, the ones in our aging audience. But is this news? Is the sky really falling?

Kyle Gann over at PostClassic blogged last December about a speech by Leon Botstein. Here's a portion of that post:

"Classical music is not in competition with any form of mass entertainment, and never has been. The world of mass entertainment has grown astronomically, but classical music has never shrunk. The size of the classical music audience, he went on, is as large as it has ever been, and it has always, since the 19th century, consisted primarily of the old, with a secondary contingent of very young listeners. He attributed this to the complexity of the classical music experience, which does not take on full meaning until one's own life has grown complicated enough to match it. Where the crisis is... is not in the size or commitment of the audience, or the expenses of production, or the education of the audience, or the quality of musical expertise, but in the location of patronage."

Although the cultural life in a few large cities may be able to support the kind of programming that will create a huge young adult audience for classical music concerts, this older demographic is and will be a fact of life for the rest of us. There's a small (secondary contingent, Botstein says) of young listeners, but they'll always be a fringe element, and they're dedicated to music for their own highly specific and personal reasons. In an environment where an entire series or group of concerts can be targeted specifically to a younger demographic (both in content and marketing), they could become the majority. But do I expect 20- and 30-somethings to come out in force for a concert series where the average age is a couple decades higher? I'm sure I'm in the minority, but I think not.

The "Younger Audience"

Is this any reason to ignore these folks? Of course not. But I believe the classical music experience manifests itself differently for them. This is where the the new opportunities - the opening "windows" - come into play. Downloads of classical music from the internet (according to Naxos last fall) account for a full 12% of all downloaded music - a much higher percentage than classical music accounts for in CD purchases, or for that matter, in live concert attendance.

From where I sit (at 49, for the record), I can see both sides.

If I hadn't been working in classical music all these years, would I have been a regular opera/symphony/dance/theatre/chamber music attendee? Hate to say it, but no. Not enough discretionary income, way too few hours in the day, too many complicated childcare logistics. In spite of missing out on the very real and enjoyable aspects of a live performance, would I have been very happy to get my fix via mp3s and satellite radio after the kids went to bed? You bet.

I now have one child in college and one in high school - am I already seeing glimpses of the day when my husband and I will buy theatre subscriptions? No doubt. I'm becoming one of those late-middle-aged (gulp) folks whose aging butts fill our seats. (Sorry for the image.... at least my hair isn't gray yet, but that's a fluke of genetics...)

The True Youngsters

I can't remember where I read this recently (yes, I am getting old), but there's a camp who believes that the reduction in arts education for children is inconsequential. (Maybe it's in Sandow's book, come to think of it...)

This is where it gets ugly. The arts absolutely have to be part of our children's lives if they're going to grow up to be empathetic, engaged, and fully human adults. This doesn't mean that they need to learn about sonata form and chiaroscuro in music and art history classes. It means that they must have repeated personal exposure and active involvement with that aspect of the arts that imprints itself on our souls and minds.

I took piano lessons from the age of 7, but one of the experiences that most influenced my continued involvement in music came at the business end of a bass clarinet. As often happens with students who read music well, I was deployed randomly throughout my high school band. I somehow ended up playing bass clarinet in a regional band, and during the beginning of a transcription of the finale to the Tchaikovsky 4th Symphony, I realized that being in the middle of that huge swirl of sound was one of the most thrilling things that ever happened to me.

If these kids have first-hand contact with musicians who are vivid, committed, and generous people, they'll remember it. If they get carried away by the experience of singing in a big choir, or thumping away at some very accommodating Orff instruments, or playing a small role onstage during a heart-stopping theatrical moment, they will remember it. And 20, 30, 40 years later, they will be our audience.

Maryland 78, Duke 75

Now, you knew I'd get back to basketball, didn't you?

What a great game those Lady Terps played. I taught briefly at Maryland, so I feel as if I can take vicarious pride. But would I enjoy basketball as much if my daughter hadn't played in high school? If I hadn't spent all those hours at scrimmages, games, and practices? No. Got the parallel? It's not the only reason that sports audiences are far larger than music audiences, but if our kids don't get close to the music, there's less of a chance they'll find a reason to make room in their lives and hearts when they grow up.

If you're still with me, I both apologize and thank you. And if you're too through with all of this philosophizing (?), I promise to return to my senses next time I write.